Lasagna

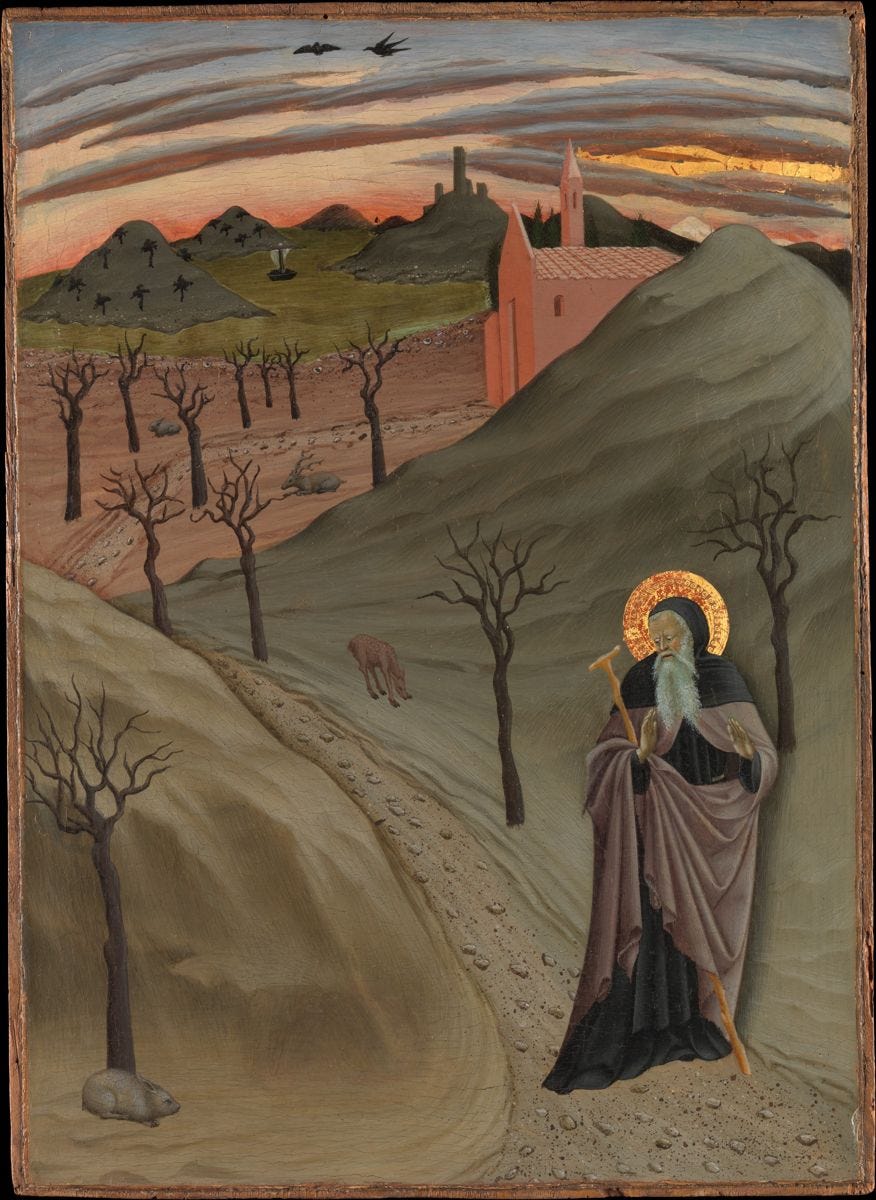

Saint Anthony the Abbot in the Wilderness, Osservanza Master (ca. 1435)

Returning to New York in October was an exercise in attempting to manage a relationship with time while being fully disoriented by it. The experience of being alive can be generally described this way, but the experience of entering the New York metro and coming from a place where time is much softer and more malleable heightens your awareness of it.

The way time moves in New York, ranging from stretched at times then suddenly compressed, like the kneading of a loaf, is made even more complex by the desire to consume as much of the city-specific food as possible within the span of your visit. No matter how long your intended stay in the city, there’s never enough time to go everywhere you want to go, to see everyone you want to see, to eat everything that deserves your close attention.

Despite only having a week’s time, an impressive and specific amount of food was consumed. The dish that stuck with me, the one that remained close to the bones in my chest after I’d returned from New York and the subsequent envelopment by the every-day, is the lasagna Marc made Halloween evening.

Paige had been suggesting that we make lasagna for weeks. I had been balking. My feelings towards lasagna were formed in the context of the unremarkable iterations that I associated with low-effort home dining, a casserole of pasta sheets―often overdone along the edge of the serving dish―and filled of bland, store-bought ingredients. It must be admitted that, in the Midwest of my childhood, lasagna served the same purpose as many other casseroles: it was easy to prepare ahead of time, easily warmed for serving, and economic in its ability to yield a large amount of food per square-inch.

As the lasagna noodles soaked in water, I stood in the doorway of Marc and Meg’s kitchen watching Marc prepare the elemental sauces. Their kitchen, a hallway barely divided from the living room and back bedroom, is typical of a Brooklyn one-bedroom, every inch of space organized for storage, the kind of kitchen where you feel every moment of careful attention that goes into a meal. We tried to figure out exactly why it is that lasagna never feels that desirable of an option when you come face-to-face with the menu at an Italian restaurant. The place that its taken as a common family home dish makes it feel too out of place for a special occasion, not enough of an event to make itself more appealing than the pappardelle with cream sauce or seafood linguine.

A steel knife with an ivory handle made in Venice, Italy (14th Century)

But this pasta casserole that would appear in the various dining rooms of my childhood contains a historical depth. As with so much food we attribute to one nationality, the modern recipe for the dish rose from the depths of all that is traditional and unwritten in the forging of the culinary habits people of many nations, fermenting over the centuries until it developed into what is recognizable today.

The lasagna’s ancestral formations are fairly unrecognizable now. Not quite as gluttonous or overflowing with flavor as the modern conception would have it, one of the earliest forms of something resembling a lasagna comes from first century Rome. In the Apicius, a collection of recipes generally attributed to Marcus Gavius Apicius (more of a symbol for the advent for the concept of a “gourmet” than an actual human that existed at one point in history), there is a recipe variety for a grand dish of layered food. The recipe, referred to in the Apicius as a “caccabinam,” calls for the arrangement of different kinds of vegetables in a casserole cooked with chicken, broth, pepper, and an egg-based dressing.

The lasagna recognizable to modern Americans came out of northern Italy in the 14th century as the medieval era drew to a close and the Italian Renaissance appeared faintly on the historical horizon. The landmark medieval cookbook Liber de Coquina contains a recipe for an early form of lasagna in its latter half, though this iteration only resembled modern lasagna in how it employed flat pasta, which was fermented and involved the use of cheese and spices.

It wasn’t until the late 17th century that tomatoes became more commonplace in Europe, shipped over along with all the wealth of diverse edible produce that came as a result of the developing intra-European enthusiasm for pillaging the American continents. One of the first cookbooks containing recipes that involved tomatoes was published in Naples in 1692, but the author credits the recipes to a Spanish source. It seems reasonable to assume that the familiar lasagne al forno would not have become a popular dish until well into the 18th century, at the earliest.

The Great Pallas Athene Dish, illustration from the Apicius

The problem with the modern conception of lasagna is that it can be almost anything. It’s a dish that requires, in its most basic form, no real culinary aptitude. This is also what makes it accessible to home cooks. The ingredients can be bought at nearly any grocery store, putting them together is undemanding, as simple as assembling the ingredients and putting it in the oven. A lasagna can be almost anything, but too often it’s something unmemorable. Overcooked pasta become becomes too brittle to the tooth in the middle while turning crusty around the edges. Under-seasoned sauce and water-saturated cheese can come together to form a melange, offensive in texture and taste.

This is not to say that lasagna cannot be remarkable. Almost any Italian restaurant, from the suburban Olive Garden or Macaroni Grill to any family-run joint or white tablecloth restaurant in Manhattan, has lasagna on the menu. It’s a dish so woven into the conceptual fabric of “Italian food” that it has nearly made itself invisible. But in the form of the dish closest to its Neapolitan origin is celebratory. In Saveur, New York chefs Albert di Meglio and Angelo Pappalardo recount how, as children, their families would make a classical form of lasagna at Christmas.

All of this lives in the modern consideration of the dish. Lasagna is often unpredictable, difficult to gauge in quality unless you’ve had it at that specific restaurant previously or know it’s been made by a trusted chef. In its ubiquity, it’s become difficult to foresee any individual iteration’s quality. But this is the heart of the dish. The Italian lasagna―referring to the singular pasta sheet, lasagne referring to the plural―is derived from the Vulgar Latin lasania, referring to a cooking pot and its contents, which in turn is derived from the Latin lasanum, or chamber pot, from the Greek lasanon. The word for lasagna is literally derived from an ancient term for a pot you put all the shit in.

Lasagna’s etymology gets at the hear of the dish’s unfixed identity. It’s a dish that took on the name of its container. The contents became conceptually inseparable from its vessel, making the vessel the only commonality across every dish that names itself lasagna. It’s a blank map, a dish with strong traditions and a history that can be totally disregarded, leaving room for a variance in preparation, execution, and quality that can result in the height of culinary achievement, deep disappointment, and, often, something in between those two poles: common, unremarkable, and unmemorable.

The Feast of Herod and the Beheading of the Baptist, Giovanni Baronzio (1330-35)

This brings me back to Marc’s lasagna, simply made and perfectly in line with the Neapolitan tradition. A sauce, somewhere between bolognese and ragu, set the tone, a blend of Italian sausage pulled from its casing made to the body-giving ground beef base a little louder. Wet ricotta and medallions of mozzarella marked each layer. A deceptively simple béchamel, prepared by adding milk to a roux, provided a richness and performed the essential function of bringing the formerly nebulous pasta, meat sauce, and cheese together as firming agent, bringing a base richness to lay beneath everything else. This is apt, as béchamel, or the Italian besciamella, has its origins in Renaissance Tuscany where it was christened “salsa colla,” or “glue sauce.”

It’s not an overstatement to say that Marc’s lasagna―fairly simple in construction but complex and rich in flavor, a textural revelation―changed the way I think about this dish. Watching him make the dish, I thought of a tradition he and Meg have developed. Whenever Marc, a bartender and an excellent cook, and Meg shared a Monday evening off, they would cook a meal together. These “Mangia Mondays” always seemed to be a conscious celebration of intimacy, two people savoring a string of moments together whose lives were bound together, but the demands put upon them by work and life were asymmetrical. If food can provide anything beyond nourishment and pleasure, facilitating intimacy seems as noble a goal as any.